We are living in an era where our one foot is in the present and the other is perpetually in the future. Modern schools aim to prepare students to face an uncertain future but do not generally equip the latter with proper historical consciousness.

For the majority of youths, any formal engagement with history ends the moment they graduate from their high schools. Little do they know that the official history learned in schools is the distorted version of the past which only reinforces the established narratives of the nation-state and the vested interests of the rulers.

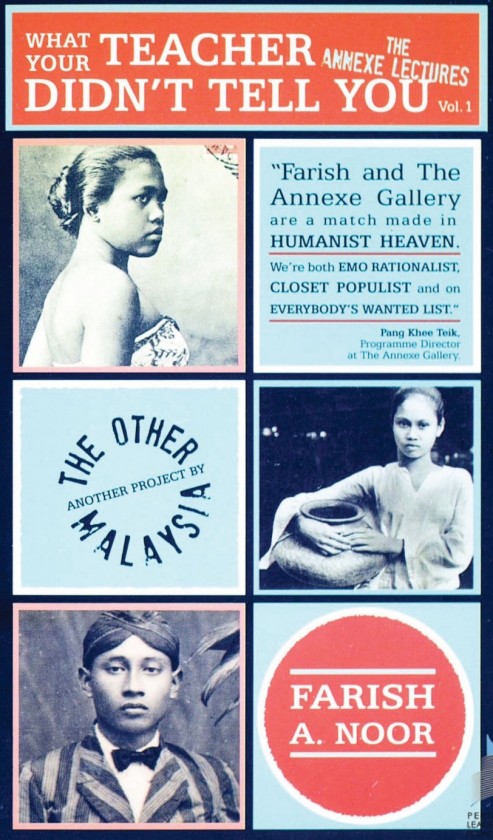

Historian Farish A. Noor's unconventional book "What Your Teacher Didn't Tell You" skillfully explores the 'untold' in formal classes discussing its varied dimensions and implications in the context of Malaysia. However, it also provides crucial insights into similar issues in the larger context of Southeast Asia.

Beyond the conventions

As a reader, the book initially intrigued me owing to its peculiar genesis, not to mention the witty persona of the writer that comes through quite brilliantly in the text.

To share what is normally not shared in formal classes, Noor broke out of the confines of formal 'academic' spaces initiating a series of public lectures titled 'The Other Malaysia' (named after his regular column) at the Annexe Gallery, Central Market in Kuala Lumpur in March 2008. He used the platform to prompt his audience to think critically about their past so that they may reclaim the discursive landscape of the country from the hands of self-serving politicians and the like.

The book originates in this public engagement project of the writer. It brings together his lecture-essays composed and delivered between 2008 and 2009. Azmi Sharom from the University of Malaya has written an enticing introduction to the book which outlines the challenge of working as an academic in Malaysia. Part of the challenge lies in teaching and researching in an environment where there is little or no academic freedom.

It should be noted that people do not pursue an academic vocation in order to make a fortune. They enter academia simply because they love teaching, researching, writing, and contributing to the knowledge production. Of course, these activities cannot always be sustained without a firm economic base. This is where the problem arises - a tension between the task of income generation and the task of knowledge production/dissemination.

While the insecurity of career may prompt academics to be obedient to the structures of power both at the micro and macro levels, their teaching and research responsibilities require them to state the truth as revealed by their analyses and research which can ruffle feathers of many hyper-sensitive people.

Academic freedom in principle secures academics from the consequences of their academic works. Unfortunately, this fundamental element of academia is often absent in many places resulting in a compromised state of knowledge production/dissemination.

In a context where self-censorship in the public domain is rife, it is commendable that Noor didn't confine his potentially controversial talks to relatively safer environment of the university spaces. He rather took the discussion to the social arena where, he insists, knowledge production actually happens. The book, therefore, may be taken as his own way of giving back to the society.

Unearthing the plural past

In contrast to the logic of nation-state with its emphasis on clear demarcation of the national boundaries and identity, the book brings to light the existence of vibrant networks that connected Malaysia fluidly with the rest of Southeast Asia and South Asia in cultural, religious, political and economic realms in its pre-modern and pre-colonial times.

Noor takes the contemporary period as a point of departure and deconstructs the taken-for-granted aspects of contemporary Malaysia by tracing their historical origins. For instance, his deconstruction of the singular image of keris, a weapon-cum-symbol representing Malay Islamic ethnonationalism today, reveals the object's composite origins with its materiality embodying the socio-cultural, aesthetic and ritual values of people following Hinduism-Buddhism (and later Islam) from Southeast Asia, India and China.

He further locates the cosmopolitan-ness of the pre-modern and pre-colonial Malaysia in the classical Malay literature, namely Hikayat Hang Tuah. Hang Tuah is celebrated as a national hero who has been depicted as a brave Malay warrior in the first part of Hikayat.

Noor contends that the second part of Hikayat, not known to many, contrastingly projects Hang Tuah as a globe-trotting diplomat who transcends all cultural boundaries to learn from the world eventually renouncing the path of violence for good. By engaging with this almost forgotten part of Hikayat, he exposes the selective parochialism of the popular ethno-nationalist narratives that invisibilize all traces of cosmopolitan imagination.

Furthermore, he shows that the conservative attitude towards the issues of sex and gender in contemporary Malaysia and Southeast Asia is of modern origin, not shared by people in the past. He establishes this point by digging into a 16th century travelogue written by Antonio Pigafetta and a popular Malay folk literature called Hikayat Panji Semirang Asmarantaka. Based on the these and other historical evidences, he argues that "as far as the spectrum of sexual identities and relations was concerned, Southeast Asian communities were far more complex, plural and tolerant than they are today" (p. 152).

The book includes a bonus chapter that dwells on the political contribution of Dr. Burhanuddin al-Helmy who took the leadership of Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS) from 1956 to 1969. The chapter traces the political trajectory of Dr. Burhanuddin al-Helmy and thereby, foregrounding the latter's progressive, non-racialist, non-communitarian and democratic credentials in national politics.

By highlighting Dr. Burhanuddin al-Helmy's brand of politics, Noor suggests the possibility of reviving his legacy to develop an inclusive and democratic model of Islamic national politics in contemporary Malaysia at a time when the country is riven by racial politics.

It is well known that racial and religious divisions in Southeast Asia, as much as in South Asia, are legacies of the colonial rule. With an aim to efficiently govern the colonized population, the colonial mode of governance arrested the fluid identities of the people by putting them into various essentialized categories through instruments like census which the postcolonial elites conveniently appropriated to suit their vested interests.

In the context of Malaysia, writes Noor, the postcolonial elites perpetuated a de facto neo-feudal regime under the garb of democracy. He argues that democracy cannot work unless citizens are able to think and talk using democratic language and vocabulary - something that is missing in the whole of Southeast Asia. The book thus underlines the need to develop a progressive political language to transcend the feudal mindset and realize democracy in a true sense.

Concluding notes

In the light of the above discussion, it is evident that the book has been titled quite appropriately. Though it is primarily targeted for general audience, the essays included in the book are marked with academic rigor and would be of immense value to anyone interested in history and anthropology of Malaysia and Southeast Asia.

The book interestingly highlights close linkages between Southeast Asia and South Asia in the pre-colonial period but this idea is relatively underdeveloped in the book.

Noor uses terms like 'South Asia' and 'Greater India' almost interchangeably in some places which is problematic from a South Asian perspective. It would have been better if he had nuanced the idea further, lest it be taken up by the rightist forces in India whose politics are oriented towards an imagined homogenous Hindu India spanning across most of South Asia - the same sort of political inclinations that he opposes in the context of Malaysia.

However, the book makes it clear that tolerance and cosmopolitanism were ingrained in Southeast Asian societies before the colonial rupture. Noor is by no means pining for a return to a 'golden period' in history which the colonial experience thwarted. Instead, he suggests that Southeast Asian people can find important lessons and inspiration from their pre-colonial past to work out any progressive agendas for the future.

Overall, the book is a thought-provoking intervention that runs contrary to the established narratives in the contemporary postcolonial Southeast Asia. Moreover, it is a significant endeavor to drive home the idea that people can consciously shape history as they are being shaped by it.

Noor, Farish A. (2009). "What Your Teacher Didn't Tell You: The Annexe Lectures (Vol. 1)" Petaling Jaya: Matahari Books.

www.facebook.com/tcijthai

ป้ายคำ